Antiracism & UDL Converge for Student Success

A classroom should be a place where all learners — not just a select few — have opportunities to succeed.

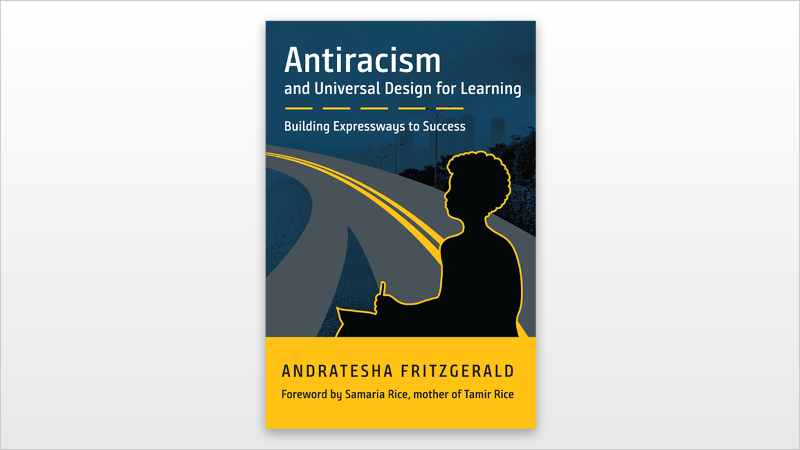

In her new book, Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning: Building Expressways to Success, author Andratesha Fritzgerald issues a challenge. She asks educators to protest school systems that benefit white, privileged students but have detrimental effects on other students. Students with disabilities, English language learners, LGBTQ students, students who experience trauma, economically disadvantaged students, and Black and Brown students.

The book from CAST Professional Publishing illuminates how to identify and eliminate barriers. It also shows how to prepare learning environments so all students — especially Black and Brown students — can succeed.

“[Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning] had to be written, and written now, because the temperature in the world is right,” says Fritzgerald, 41, Director of Teaching, Learning and Innovation in the East Cleveland City School District. She also works as an education consultant, online course instructor and virtual module content provider with Novak Educational Consulting.

Book Foreword by Tamir Rice’s Mother

“People are looking for ways to make changes that make the world better,” Fritzgerald says. “[Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning] tells teachers who teach Black and Brown children what it means to honor a child in your presence. [It also tells them] what it means to bring out the best in them, and what strategies you can use to reach them, to teach them, and also to learn from them.”

The book’s foreword is written by Samaria Rice, mother of Tamir Rice, whose death at age 12 by a Cleveland police officer in 2014 spurred activism in the community and beyond. Fritzgerald wanted to partner with Rice because of her message of reform in policing. She also loves that Rice champions arts education, after-school programming and community wraparound services.

“[Rice’s] voice is important, because she knows what happens if we don’t change this world,” Fritzgerald says. “She knows the tragedy of brutality that hits really close to home. It was important to give her the space to share with educators some thoughts that really empower them and to get them to come to the sobering reality that what you do in the classroom changes lives forever.”

Book Spotlights Lack of Educational Justice

Fritzgerald’s book spotlights the lack of educational justice in schools. It also details what happens when classrooms are not culturally responsive, culturally sustaining, flexible and empowering.

According to research cited in Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning, data shows:

- Black students get suspended at a rate more than 3 times higher than white students.

- They are nearly three times more likely to be held back as their white peers, when combining data for all grade levels.

- The average Black 12th-grader places in the 19th percentile in math and 22nd percentile in ELA, and these statistics have remained nearly unchanged for about 50 years.

Antiracism and UDL Start with Honor

Antiracism must be active, not passive. Universal design has to be intentionally implemented — not just intended. Success for all must be more than passion. It has to be power by empowerment!

Andratesha Fritzgerald in Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning: Building Expressways to Success

It’s up to teachers and schools to create learning environments that uphold honor and allow students to learn and lead. “Every act that serves Black and Brown children better is an act of antiracism,” Fritzgerald says. “When we design with every student in front of us in mind, that is Universal Design for Learning. When those two roads merge, that’s when truly there is liberation and freedom in the classroom.”

But change must be purposeful.

"If we do nothing to change, then we are practicing dishonor to Black and Brown children," Fritzgerald states in her book. "We are encouraging their failure and embracing a system that has proven to be racist for as long as schooling has been in existence."

A Turning Point In Her Teaching Career

Fritzgerald witnessed firsthand what happens when teachers honor learners. It was her first year as a high school English teacher in the East Cleveland City School District. She told a veteran teacher she was struggling to reach a particular group of students. The teacher’s response was to “load them up” and give them a ton of work.

After taking that advice, an 11th grader in Fritzgerald’s class raised his hand and told her something she says almost haunted her. “You’ve given us a lot of work,” he said. “And we could do it, but we’re not learning anything.”

“That was a turning point in my teaching career,” Fritzgerald says. “It was a turning point in how I thought about what I was asking students to do. How I shaped and designed lessons. It was an opportunity for me to honor the feedback I didn’t know to ask for, but I definitely needed, and to never let that opportunity pass again.”

Growing Up with Role Models in Education

When Fritzgerald was a student, several teachers showed her the transformative power of what can happen in the classroom.

Fritzgerald’s kindergarten teacher, who later became her principal, expected excellence and greatness from her students. Her 6th grade teacher, Ms. Stephanie Tome, was her first UDL experience. Tome had personal relationships with each student and would turn learning into songs or games. She rekindled Fritzgerald’s love of learning, turning around negative experiences from the year before.

Fritzgerald’s 9th-grade English teacher Mrs. Kuhn showed her what can happen when students are free to express themselves in authentic ways.

In a final assignment on Romeo and Juliet, students picked a project from a sheet of options. Fritzgerald chose to write a rap from the point of view of one of the characters in the story. Her teacher loved Fritzgerald’s project so much, she kept the tape and played it for every single class. She also encouraged her to write for the school literary magazine and publish her poetry.

“You learn so much more when you’re free to express your learning in a way that makes sense and is not contrary to who you are,” Fritzgerald says. “I didn’t have to change myself to be successful in her classroom. I didn’t have to compartmentalize my identity to learn and express my learning. There was a freedom I experienced.”

UDL Strategies Impact All Learners

Fritzgerald and a team of East Cleveland teachers explore Boston after a UDL workshop with Dr. Katie Novak.

In 2015, Fritzgerald attended a UDL workshop sponsored by a local educational services center. The day’s presenter was Dr. Katie Novak. As Fritzgerald listened, she thought, “This is how I teach [and] what I want for other teachers. [UDL] gives a name to the strategies that have been so powerful and impactful for me and for my students over the years.”

After that, she bought every UDL book she could find. After receiving permission from the superintendent, Fritzgerald and another colleague worked with Novak to create a custom course for teachers in their district. Teachers could personalize their own professional development learning experiences in the course. This showed them how they could do the same for their students.

From there, Fritzgerald’s involvement in UDL multiplied. Besides her current positions, Fritzgerald also is a speaker and writer. She contributed a chapter to the book, “What Really Works with Universal Design for Learning,” published in 2019 by Corwin Publishers. Fritzgerald also co-wrote the article “Equity in our Schools: A Pretty Little Lie” on the Think Inclusive website. She was featured twice in Education Week.

A Great-Grandmother Who Valued Education

(Left) The author's great-grandmother, Amanda Smith. (Right) Smith’s books behind her, Fritzgerald poses in cap and gown for her very first graduation — from preschool in 1983.

One of Fritzgerald’s life influences was her great-grandmother, Amanda Smith. Fritzgerald grew up in inner-city Cleveland near downtown, and was constantly surrounded by books as a child. Her great-grandmother was responsible for getting Fritzgerald to and from school. She would ride public transportation with her — always with a book in hand.

“Even before I could read, I wanted to read,” says Fritzgerald, adding her great-grandmother taught her and her sister how to read and write.

Smith had a reason for valuing education. Born in rural Bessemer, Ala., Smith’s mother was the daughter of slaves and illiterate. By contrast, Smith’s father was an educated sharecropper who attended and, according to family history, taught courses at Tuskegee Institute.

The Importance of Respect

When Smith was 8, her father died and she moved north during the Great Migration with her mother and siblings. Smith had great intellectual capacity and could academically perform so well, she was subject to teacher criticism. Her teachers disrespected her by refusing to call her by her given name and using a nickname. As a result, Smith always advocated the importance of addressing people in a respectful way.

Smith told her great-grandchildren how her mother had to sign her name with an “X.” “My great-grandmother would literally spend hours preaching to us ‘Here is the power of education,’” Fritzgerald recounts.

“‘You can read your own contracts and sign them with your name; you will know what it is that is in front of you. And without this, you don’t know what people are saying to you.’ She would take the time to make sure we understood the power we had when we knew how to read and how to write.”

Transmitting Knowledge to the Next Generation

Passing down a love for the written word: The author with her husband, Tony, daughter, Lani, and son, Tony.

Fritzgerald herself is passing down a love of the written word. Her family — including husband Tony and their two children, Tony and Lani, ages 12 and 13 respectively — reads books and enjoys creating things together. They also love traveling and road trips.

“She taught me that no matter what people think of you and no matter what box they try to put you in, you have to honor yourself and believe you can do more,” Fritzgerald says of her great-grandmother. “Her example of resilience and knowledge, and the importance to transmit that knowledge to the next generation and the next generation, really instilled in me to keep her legacy alive and tell her story.”

A Passion for Urban Education

Needless to say, Smith was delighted when Fritzgerald became a teacher. Growing up, Fritzgerald was convinced she was going to be an engineer. During her early years of college at Cleveland State University, she did internships at NASA, the university’s Chemical Engineering department, and Polytech.

“It just didn’t spark a passion that one needs to commit to it for a lifetime,” she says. She switched her major to English.

One college summer, she worked as a resident coordinator for Upward Bound, a federal TRIO program for low-income or first-generation potential college students. She lived with 100 high school students for six weeks.

“At the end of that summer I was exhausted, but I realized I spent every moment of that summer happy,” Fritzgerald says. “I thought to myself, I could work with kids forever.”

Later, when she saw a flyer for a master’s program in Urban Secondary Teaching, it sparked her passion.

Fritzgerald earned a bachelor’s degree in English with a minor in Women’s Studies and a master’s degree in Urban Secondary Teaching with a focus on curriculum and instruction. She also has an Education Specialist degree in Administration. All three degrees come from Cleveland State University.

Using Antiracism and UDL to Reach All Students

Two of Fritzgerald’s English students, Teauna (left) and Tyisha, at their high school graduation.

While teaching English for seven years in the East Cleveland City School District, Fritzgerald utilized nontraditional methods and gave students a lot of choices.

As an example, she remembers one class where students were able to express themselves in meaningful ways and discover one another’s talents. Students elected each other to classroom roles, based on their own strengths. Although her students were in a low-income urban district, 93 percent of her students passed the state test.

“There was this community of honor. We honored one another,” Fritzgerald says. “There was so much respect in the room. We really learned from one another.”

Honoring children puts them in the driver’s seat, Fritzgerald says. “We don’t want children to learn just for the sake of pleasing the teacher, but for the sake of reaching their goals, making it to their destination, and really focusing on goals that are deeply personal in a way that’s relevant and authentic to them.”

A Teacher Circle That Provided Support

Says Fritzgerald of her teacher circle: “I learned the power of collaboration.”

In the same way, teachers developed a sense of community with each other.

Fritzgerald credits her teacher circle with providing support, feedback and inspiration in those early years of teaching. They included social studies teacher Lori Urogdy-Eiler, Spanish teacher Krissy Longino and Sandra Benjamin-Walker, who taught students with disabilities in a self-contained setting.

“I learned the power of collaboration and not going it alone,” Fritzgerald says. “This is not work you can do alone — that’s how you burn out quickly. Find your people who will lend their strength to you and accept the strength from you to them, and that’s what makes a difference.”

Fritzgerald filled Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning with personal stories about what she’s learned, experienced and facilitated. “Those are the defining moments in my career that led me to want to see that kind of access, that kind of success, for all Black and Brown students,” she says.

Antiracism and UDL Emphasizes Honor for Every Student

Throughout Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning, Fritzgerald emphasizes the importance of mobilizing honor, instead of power that yields compliance.

“Power actually pushes people into compliance,” Fritzgerald says. “Honor pulls out the genius in everyone that’s in front of you. When you look at the compliance issues that are created, that all screams power.”

As she puts it, it takes bravery, guts and rebellion to actualize the dream of access and success for all.

“Antiracism is active and not passive,” Fritzgerald says. “It is a series of choices built out of a passion for equity. Knowing the consequences [of not choosing] antiracism should fuel us to empower Black and Brown children to succeed.”

Fritzgerald explains that students never come alive because they’ve been suspended, excluded from an activity or told they are deficient.

“What I hope teachers take away from the book is that if they honor every child who walks into their classroom, if they give Black and Brown students an experience with success they’ve designed for them, then they’ll see that creates an expressway to success, and success defined by the students’ terms.”

It’s a clear contrast to the current way of educating in the majority of classrooms across the country. “We know the results that power gets,” Fritzgerald says. “But honor unlocks the results yet to be fulfilled.”

Order your copy today!

Antiracism and Universal Design for Learning by Andratesha Fritzgerald is available in paperback ($29.99, 192 pages) and accessible EPUB ($29.99) format.