Higher Education Author Advocates for UDL

Universal Design for Learning concepts implemented at the K-12 level don’t necessarily transfer to higher education.

Both groups face different barriers, says Dr. Eric J. Moore, co-author of a new CAST book, UDL Navigators in Higher Education: A Field Guide.

“We have to account for adult learners who may be balancing significant school, life and work commitments,” he says.

Dr. Moore, 36, has taught middle school through college in the U.S. and abroad. He says UDL requires a true culture change.

“Culture in a K-12 school can be changed with some haste with a strong administrator who can win over and help guide teachers into a certain model of teaching,” Dr. Moore explains. “Higher ed faculty tend to be far more independent and siloed.”

Changing culture in higher education doesn’t usually begin with high-ranking administration, he says. Instead, it begins with grassroots energy, recruiting administrators much later in the process for practical reasons.

“But UDL in higher education also affords unique opportunities, as learners are often more mature, self-aware and focused on their ambitions,” says Moore, now a UDL and accessibility specialist at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville.

In addition, he is co-owner and consultant of Innospire Education, and regularly serves as a UDL consultant. “With coaching, these qualities can be harnessed to support their capacity as decision makers.”

A Typical Day Using UDL in Higher Ed

Moore in his office, digging into UDL Theory and Practice for the umpteenth time.

A bedrock aspect of Moore’s UDL strategy at UT-Knoxville has been relationship building. He did this first with co-workers on his instructional design team. Now he’s working to establish deep connections in areas like Teaching & Learning Innovation, Student Success, and Student Disability Services.

“I believe — as David Rose does — that UDL is culture change,” Moore says. “That change of culture requires a common language and value system across campus that cannot be centralized in an individual. It’s all about developing and enriching a team!”

He says his work involves infusing UDL principles throughout the process of constructing course design with faculty. This might involve converting course objectives to outcomes that are clear, purposeful and motivating from a student perspective. Or it could mean considering variability in the design of effective assessments, methods and materials.

At the same time, Moore says his targeted one-course-at-a-time approach can only go so far. “I have also been working to develop synchronous and asynchronous training opportunities for faculty, staff, and students,” he says, noting his Implementing UDL on Canvas course. “I lead workshops frequently as a way to get faculty started and encourage them to work with me more.”

A Decade of Learning About UDL

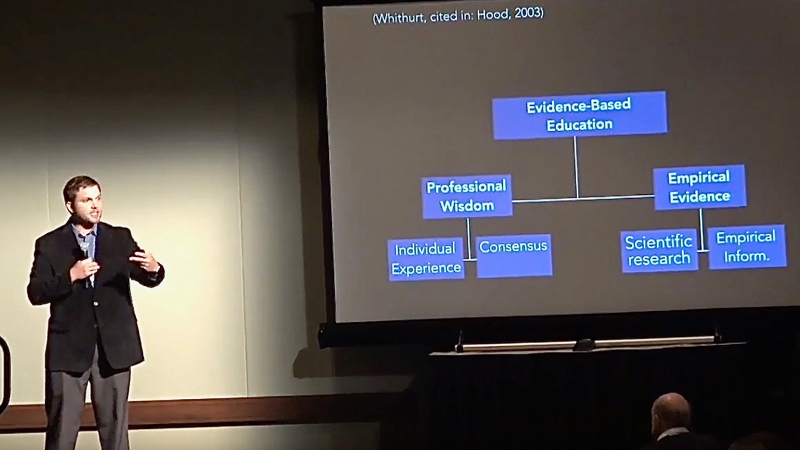

Moore had the joy of leading a “UDL talk” at the UDL-IRN Summit in 2017.

Moore, who holds a PhD in Inclusive Education from the University of Tennessee, discovered UDL through a colleague in 2010. He was teaching in South Korea while working on his master’s degree from Grand Valley State University in Michigan.

He learned how the UDL philosophy empowers classroom teachers to design lessons that account for the predictable variability of their learners. As someone who began losing his hearing in middle school, Moore says he would have benefited from UDL as a student who needed to adapt how he learned in the classroom.

Before Moore learned how UDL works, he spent time researching and reviewing other frameworks and models designed for secondary education. He eventually realized the way he learned to instruct American students didn’t necessarily apply in classrooms across the world.

“It seemed more holistic, and more practical than many of the solutions I had attempted up to that point,” says Dr. Moore, who grew up in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Searching for the ‘Holy Grail’ of Teaching

Teaching in Indonesia before moving to South Korea, Moore loved working with students from diverse backgrounds.

He didn’t want a lesson plan that would show students how to memorize and regurgitate a set of facts. He wanted to help his students engage with novels, plays, and other mediums and to encourage them to think for themselves. “It was an ongoing search for the Holy Grail that would let me teach students effectively,” he says.

CAST originally developed UDL in the 1990s as a tool for special education classrooms, crafting lesson plans around a student’s abilities. Researchers ultimately realized the philosophy can be applied in general education classrooms as well.

Moore started using the UDL principles in his South Korean classrooms, designing lessons that gave students more flexibility. He began to see himself as a facilitator, equipping students to learn for themselves and make their own decisions.

“I began to realize the goal was to develop [students’] passion and appreciation for literature, not necessarily have them make the same choices I would make myself,” he says.

Teaching Students How to Take Ownership

Moore’s appreciation for crafting lessons to engage all students blossomed when he began losing his hearing in middle school. Today, Moore doesn’t hear naturally, though he doesn’t use the term “deaf” to describe himself. “I would say I am hard of hearing,” Moore says.

He hears through a cochlear implant, but if the device is damaged or the batteries unexpectedly die, he remembers how fragile his dependence on technology really is.

In middle school, Moore had to deal with the social ramifications of other students making fun of him for wearing bulky hearing aids. He also was labeled as a student who needed an individualized education plan, or IEP. He soon realized the accommodations provided in the IEP provided more correction than what he needed.

Seating him in the front of the class would have been sufficient. Instead they moved him to a different classroom, further isolating him from his peers. “[They] did more to make me dependent than they did to teach me how to live as a person with a disability,” he says.

Providing too many resources can make students dependent on extra help as opposed to making them feel in control. “Ultimately, that can backfire when people graduate and move on to their post-formal education world and find those supports are no longer available,” he says.

Instead, UDL enables educators to teach students how to take ownership of their circumstances and advocate for themselves. For example, encouraging a sophomore who can’t understand the teacher to move to the front of the class.

Growing the UDL Higher Education Community

Moore with co-author Jodie Black.

Moore co-wrote UDL Navigators with Jodie Black after meeting her at a UDL conference in 2017. They both understood that UDL is still a relatively new concept in higher education. Their goal is to support teachers using the philosophy.

“We want to equip these people and sustain their efforts,” Moore says.

The book serves as encouragement to educators, letting them know the practice is spreading and others are seeing the benefits. It also guides educators through how to share what they’ve learned about UDL with teachers, school systems and students.

It would have been relatively rare to find anyone in higher education utilizing UDL as recently as 2012. But now universities nationwide are starting to study and engage its philosophies. It’s not just in departments of education, he says. It’s also spreading to other academic departments and even non-academic areas.

“The growth has been exponential,” Moore says.

Order your copy today!

UDL Navigators in Higher Education is the third title in the CAST Skinny Books™ series.

UDL Navigators in Higher Education: A Field Guide is available in paperback ($17.99, 126 pages) and accessible EPUB ($17.99) format.